Patients–health care consumers–can be too clever by half. Too skeptical of the motives of health professionals, hospitals, insurers, and government, many patients appear to make a habit of ignoring medical advice. They think they are smart to do so.

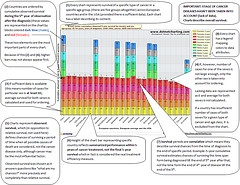

Example of Cancer Guideline

The gap between the conventional wisdom of the health establishment and the defiant doubt of many patients is explored in a recent article, wittily entitled “Evidence That Consumers Are Skeptical About Evidence-based Health Care.”

There, author Kristin Carman and colleagues suggest it will be hard to persuade consumers to accept treatment based on clinical guidelines, also called “protocols” or “best practices.” Why? In a multi-pronged study, the authors found:

. . . there is a fundamental disconnect between the idea of evidence-based medicine and many consumers’ beliefs, which don’t account for variation in quality among providers [that is, the idea that some doctors are better at some things than others] and don’t allow for cost-effectiveness [the idea that some medical procedures are worth what they cost, while others aren’t].

In other words, a lot of patients (are you one?) think any advice to forgo a particular treatment or procedure is based mainly on the economic interest of the source of the advice. I for one have run into this attitude a lot:

- Patients and families insist on futile and heroic measures at the end of life, because they think recommendations for hospice or palliative care are intended to save money, rather than improve quality of life.

- Patients (I’ve seen this in my own family) unnecessarily suffer debilitating medical conditions rather than go to doctors, who they think are just interested in making money.

- People ignore public health recommendations to get flu vaccines, even during flu epidemics, because they don’t trust the recommendations or assurances that the vaccine is safe.

- Heavily influenced by ads, many patients insist on expensive new drugs, when their physician wants to use an older, cheaper drug that is safer and just as effective.

- For years, many HIV-positive African-Americans and Africans refused retroviral treatment, because they believed that HIV was a ruse created by whites to cover up their diabolical role in infecting black communities with AIDS.

The issue is important. There’s a movement afoot to create and enforce more evidence-based guidelines, which already are often used in cases of heart attack, stroke, HIV/AIDS, and other conditions. These protocols are called “evidence-based,” because they reflect findings about what happens to most patients who receive a particular treatment as opposed to other treatments. Resistance to guidelines will forestall improvements in the quality of care.

A vicious cycle will result. First, people will be sicker for not following the guidelines. Second, many doctors will take their cue from patients and will ignore guidelines, too (doctors already ignore them far too often). Third, organizations won’t bother to develop new guidelines, since developing them takes a lot of work, and there’s no point writing guidelines that will be ignored.

What can you do? When you and the doctor are discussing your course of treatment, ask whether any clinical guidelines have been developed for your condition. After all, you want care that meets the most recent, most evidence-based standards. Why not the best?

Take care.

Photo credit: sniperslaststand3. Attribution.

Posted by New Associates

Posted by New Associates